Tags

Charles Kiernan, Csenge Zalka, fairy tale, fairy tale lobby, fairy tales, mary grace ketner, megan hicks, national storytelling network, Robin Bady, Shakespeare, storytelling, Vasilisa

Two hundred years ago, audiences laughed at this interpretation (which makes the author’s stomach churn) of Shakespeare’s classic comedy. The play is still being produced, but drastically re-interpreted. That’s art for you!

Simplia made her pronouncement, folded the letter from Activist in Oslo (see sidebar for content) and handed it across the table to one of the Magical Friends.

For once, what she said made sense to Sagacia. “Yes! There is no final, correct interpretation of a fairy tale.”

Charles Kiernan, a fast reader, finished the letter and passed it on. He said:

Fairy tales, almost by definition, are dated. They reflect an older order of things.

Emily Dickinson is dated.

Jane Austin is dated.

Shakespeare is dated.

Why do we read them?

Not because they are dated, but because they speak to us. Art, of all sorts, speaks to us through a universal language, the grammar of which cannot be methodically parsed.

Let me parse “Rapunzel.” She is a young female, whose story assumes she cannot control her fate. Her fate is in the hands of others. Her one attempt at control, which is a deceit against Dame Gothel, fails. She needs to be rescued by her prince, who knows her gentle qualities.

Let me parse “Rapunzel” again. We see a person—sheltered—who glimpses a greater world, an alluring world, to have it senselessly snatched away, and be punished for having knowledge of it.

I suggest the second parsing resonates a universality that crosses over the barrier of years.

As she finished reading the letter, Tarkabarka bristled and said:

I think saying every fairy tale is the same would be oversimplifying the diversity of world folklore. There are tales that talk about non-traditional families of all kinds, you just have to look in the right place. For example, Gay Ducey tells an amazing folktale called the Fish-wife and the Changeling Child where the stepmother is better than the real one. Also, there is a folktale motif for gender-switching where trans-gender prince loves a princess (and even gets a child with the help of a wise man). Or Aristophanes’ tale of the origin of love, is a classic.

…(I)t is just the storyteller’s responsibility, when, how, and how often he or she uses these tales together with “traditional” models. It is not really the lack of sources that makes these tales less well known – it is the lack of choice to tell them.

The Simpletons nodded enthusiatic agreement. Simplia was so enthusiastic that she managed to slosh tea onto the table. She picked up her napkin to wipe it up and noticed that Mary Grace Ketner had scribbled some notes on the underside of the napkin. It wasn’t a response to Activist in Oslo’s question about whether or not fairy tales, with their antiquated world views, served to create a sense of disenfranchisement among non-traditional families; but it was relevant.

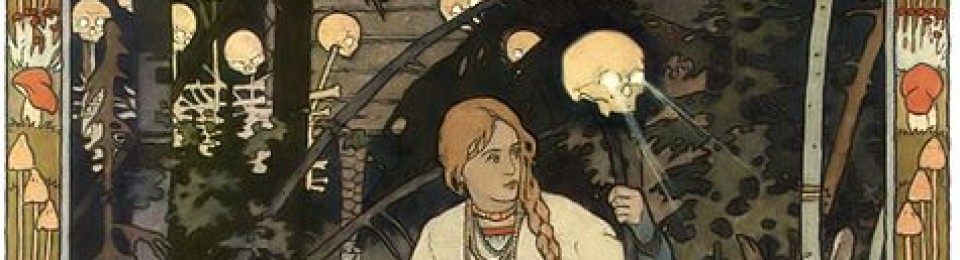

Often, while I am telling a story, I am thinking…(o)h, if only I had time to emphasize this, to make sure they understand how important the king’s decision is in the course of the story! Oh, if only they could get the full picture of Baba Yaga, her harshness and her fairness, so impossible to relay in just one story! Sometimes it feels like the stories are not whole at all but, rather, filled with teasers!

Megan Hicks had been eavesdropping from the shelter of a wingback chair near the fireplace. She peeked around the wing and said, “Fairytales are a lot like the Bible and the U.S. Constitution (especially the Fourth Amendment). In order to keep from becoming fossils, their only hope of staying relevant is to be nurtured with curiosity and an open mind. Maybe that approach was easier in the days before everything was written down, when we relied more on our ears and memories.”

Sagacia looked at the clock on the wall and started gathering her things. “Let’s continue this discussion tomorrow,” she said. “We’ve got to get going or we’ll be late.”

“Oh, yeah!” Simplia remembered. “The high school play. It starts in fifteen minutes.”

The barrista asked, “Aren’t they doing a Shakespeare comedy this time?”

Simplia said, “Yep. The Taming of the Shrew.”

Waiting with bated breath to see what you make about the Taming of the Shrew. I’ve been struggling with that story for years! Part of me thinks that it’s a story that should be ripped out of every anthology for the way it suggests that women (or people of any other gender) should be kept in their place by violence if necessary, but the other part of me thinks that it’s a story that should be told often, and urgently, and right now, in a time when people forget that it’s more important in a relationship to get on with each other than to be in the right. And as a storyteller I think that every story should be told so that every interpretation is implicit in the telling; because then people can take the message they want and need from it. But I don’t want to tell a story that allows people to think they can offer violence to their spouse (of whatever gender: or even their dog and their donkey, who both come off quite badly in the Grimm version). How would other people treat the story? Whenever I try and tell it without being horribly sexist, it just comes out prim and moralistic.

I’m right there with you, Marion. I’ve seen a couple of productions of “Shrew” that used physical comedy to turn Petruchio into a blustering clown. And while searching for an image for this post, I ran across promotional photos of a production where the Kate and Petruchio are transgender, which can’t help but throw some lovely irony and ambiguity into the mix. But the words lying there silent on the page, fed only by my imagination and past experiences, are too uncomfortable for me to even read.

Mary Grace is up next, and I don’t know if she’ll decide to run with the “Taming of the Shrew” thread or if she’ll take up Robin Bady’s comment to her initial post (which is wonderful, but I was already running at 500+ words, and you know what they say about the soul of wit), or how she’ll decide to write about it. I do know that I’m not going any further with this knotty little thread. I just threw it in there to emphasize the point Charles Kiernan made.